Those of you who have read my reviews of The Springheel Saga (Series I and II) will be familiar with the name Wireless Theatre. The company produce high quality radio drama, which is made available via download from their website. If you enjoyed Springheel Jack, or if you are a fan of alternate history tales, then you probably won’t want to miss this new mystery series.

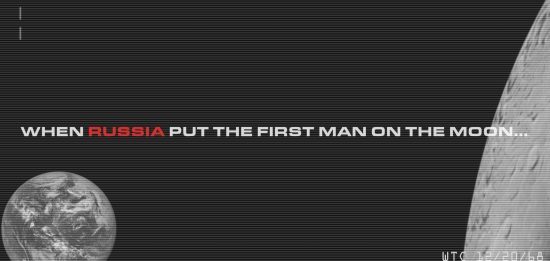

It Monday, 3 December 1979, and Eddie Sloper is getting ready to go to work. However it is not a 1979 any of us remember. The split that created this timeline happened in 1968, when Yuri Gagarin became the first man on the moon. With lunar bases and the moon being weaponised with nuclear warheads, the arms race between the US and the Soviets has expanded off-planet, with the result that the doomsday clock is now very close to midnight.

Eddie works for the British Space Liaison Department and much of the action in the first episode takes place there with very convincing performances from Philip Bulcock (Eddie) and Stephen Critchlow (as Eddie’s boss, Wilkins). However, a lot of the soundscape of the piece is in the form of news reports which fill us in on both the background history and the continuing arms crisis. I love the little details that has been added as well, such as Sid Vicious being on trial for murder (when in our timeline he had been dead for months), and the ad for “Space Snacks,” which sound like something I once purchased in the Cape Canaveral gift shop (pizza and ice cream were the two I bought).

As usual, this is a slick production, with excellent work from everyone on the team. In particular the music, by Francesco Quadraruopolo, and the overall sound design, by Jim Sigee, contribute greatly to the atmosphere of the piece. Furthermore, there is a very good balance between events on the world stage and Eddie’s story, whilst his voiceover helps to bring everything together.

Episode 1 ends on a cliffhanger, with a murder which will no doubt drive a lot of the action in further parts of the series, but don’t worry, because Episode 2 is available already, so you won’t have to wait to see what happens next!

Episode 1 of Red Moon is free to stream on Wireless Theatre’s audioBoom channel: https://audioboom.com/posts/6549173-red-moon-episode-one-moonrise-audio-drama.

Episode 2 and all further episodes are exclusive to the Wireless Theatre website: https://www.wirelesstheatrecompany.co.uk/product/red-moon-phase-ii-umbra/, with Episode 3 being released in March. The story was conceived by Jack Bowman and Robert Valentine, with the latter also writing, directing and producing.

Mary Tynan

Cover art by @arbernaut