Geraldine McCarthy lives in West Cork. She writes short stories, flash fiction and poetry. Her work has been published in various journals, both on-line and in print. This is her third appearance at Notes From Xanadu.

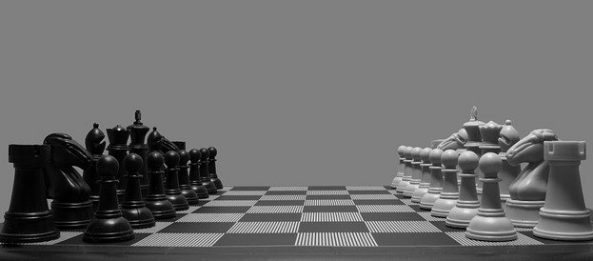

Ar bhord íseal sa tseomra suite bhí an clár fichille. É foirfe fós, na píosaí go léir ina n-inead féin. Bhí Daithí ina shuí sa chathaoir uillinn, ag fanacht le go n-imeodh an teannas as a chuid matán. Bhí sé tar éis lá cruaidh a chur isteach, fear mar é, go raibh mórán idir lámha aige. Chaith sé braon fuisce siar. Dhóigh an leacht a scórnach, ach b’in é a bhí uaidh.

Ar bhord íseal sa tseomra suite bhí an clár fichille. É foirfe fós, na píosaí go léir ina n-inead féin. Bhí Daithí ina shuí sa chathaoir uillinn, ag fanacht le go n-imeodh an teannas as a chuid matán. Bhí sé tar éis lá cruaidh a chur isteach, fear mar é, go raibh mórán idir lámha aige. Chaith sé braon fuisce siar. Dhóigh an leacht a scórnach, ach b’in é a bhí uaidh.

Ag an am seo den oíche, ba nós leis a mhachnamh a dhéanamh. Bhí tábhacht leis an oscailt is bhí stráitéis ag teastáilt. Gan méar a leagan ar aon phíosa, d’oibrigh sé amach ina cheann cén treo ina raghadh sé. Ar deireadh bhog sé an ceithearnach bán chun tosaigh i lár an chláir. Imirt chlaisiceach, ach ba dheacair é a shárú.

*

Bhí fhios ag Daithí go dtéadh Peaidí Ó Dónaill ag spaisteoireacht gach lá i ndiaidh lóin. Canathaobh nach raghadh sé fhéin ar shiúlóid chomh maith? B’in Peaidí ar bhóthar an chósta agus é ag féachaint amach ar an bhfarraige cháite .

“Conas tá agat, a Pheaidí?” arsa Daithí.

“A, mhuise, ag treabhadh liom,” arsa Peaidí.

“Is conas tá an cúram?”

“Táid ag déanamh dóibh fhéin anois.”

Thosnaigh an bheirt fhear ag siúil.

“Bhíos ag cuimhneamh fé thigh do thuismitheoirí ar an sráid mhór.”

Stop Peaidí aríst. “An raibh, anois?”

“Ní bheadh fonn ort é a dhíol?”

“Ní bheadh. Sin tigh mo mhuintire, is beidh sé ag mo chlann im dhiaidh.”

“Raghadh cúpla árasán isteach ann go deas néata, mar sin féin.”

“Níl sé ar díol, a Dhaithí.”

Tháinig faoileán anuas chun breith ar cheapaire leath-ite a bhí caite ar chiumhais an bhóthair.

“Ach gheobhainn praghas maith duit.”

Chroith Peaidí a cheann. “Mar a deirim, níl sé ar fáil.”

D’fhágadar slán ag a chéile is chuaigh Daithí thar n-ais chuig an oifig.

An oíche sin, áfach, d’fhillfeadh Daithí ar an bhficheall.